The Lucky Sportsman

Maker

George Morland

(British, 1763-1804)

Collections

ClassificationsPAINTINGS

Date1792

Mediumoil on panel

Dimensionspanel: 11 7/8 × 9 3/4 in. (30.2 × 24.8 cm.)

frame: 18 × 16 × 3 in. (45.7 × 40.6 × 7.6 cm.)

SignedSigned and dated upper left: 1792

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of the Friends of The Huntington

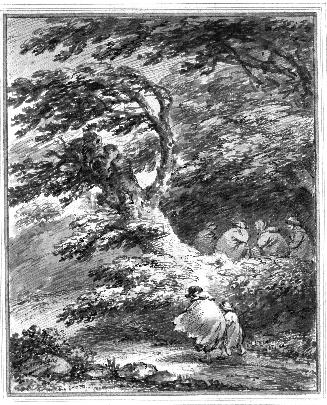

Label TextThis painting and its pendant (The Unlucky Sportsman, 58.5) subtly undercut competing stereotypes of the country sportsman. In the first of the pair, The Lucky Sportsman, two seated women encounter a man dressed in a green hunting costume with red collar and a battered hat, who leans on his rifle with his dog at his side. On the face of it, the painting upholds the traditional association of the sportsman with an ideal of warm-hearted generosity. In popular rural legend, the benevolent sportsman could be relied upon to offer charity to vagrants encountered in the woods and fields--an ideal that informs the central motif of John Wootton's painting of c.1730, A Hunting Party Giving Alms to Gypsies in a Wooded River Landscape (private collection). However, the sportsman also had a bawdy alter-ego in popular music and imagery, in which he was often portrayed as a drunken and lascivious habitué of country alehouses, where he preyed on women, as he preyed on game. Morland was perhaps England's most prolific painter of the sportsman's milieu, and his paintings reflect an intriguing ambiguity about the interpretation of this controversial figure. In one of several versions of The Benevolent Sportsman (1791), for example, Morland's biographer William Collins noted that the beneficiary of the sportsman's charity was "a little girl, the mother of whom is rather too handsome for either of her companions in the distance; and we might be apt to doubt the sportsman's motive, if his back was not turned upon all that group." The same submerged sexual implications seem to underlie The Lucky Sportsman, in which no alms are distributed, and the sportsman's "luck" evidently lies in having stumbled upon the attractive blonde woman seated nearest the viewer. Morland calls our attention to her through the eye-catching red of her riding cloak and the bright light that he trains on her face and figure. The woman's companion, whom Morland relegates to the shadows, nurses a baby, presumably the result of her own previous dalliance with an ulteriorly motived "benevolent" sportsman. As in many of Morland's paintings, there is a perplexing starkness to this encounter. The figures lack the legible gestures and facial expressions that would allow us to interpret their interaction--a deficit that Morland's engravers often felt obliged to remedy by taking artistic license with his figures. Contemporary critics faulted the artist for failing to integrate his figures coherently, but John Barrell has argued that Morland employed this lack of cohesion to express social tensions. In the present instance, the detachment of the figures leaves us in suspense as to the outcome of their meeting.

The answer is provided in the companion painting, The Unlucky Sportsman, which undercuts the myth of the merrily wenching carouser. Although the sportsman is seated in an alehouse, the toppled jug before him has evidently been used to drown his sorrows. His dejected pose, with his head buried in his arms, is an instance of the unaffected naturalism for which Morland's rustic figures were valued by his contemporaries. The sportsman's state of mind is further glossed by the image of a hanged man that appears just above and to the left of his head. As in the companion picture, his physical posture is echoed by his faithful dog. Indeed, the repetition of the dog and of the hunting costume indicates that we are looking at the same man in each picture, and that the sportsman who was "lucky" at one moment has become "unlucky" in the next. The framed pictures on the wall may comment on this inversion; the horse and jockey suggest the uncertainty of a horse race, and the juxtaposition of the crowned monarch with the oafish men seated below comments ironically on life's inequities.

Juxtaposed against the romantic intrigue of The Lucky Sportsman, this picture reads as the sequel to a failed romantic conquest, for instead of enjoying the company of two attentive women, the sportsman now shares the canvas with a pair of men who choose to ignore him. It is likely that the broken clay pipe lying at his feet is an emblem of sexual impotence. The emblematic quality of such details suggests the influence of Dutch genre painting, but William Hogarth's modern moral subjects were probably a more immediate influence. Indeed, David Solkin has made an apt comparison between this pair and Hogarth's Before and After of 1730-31 (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge), which depict the altered psychological relationship of a young woman and her seducer in the prelude and aftermath of their sexual encounter.

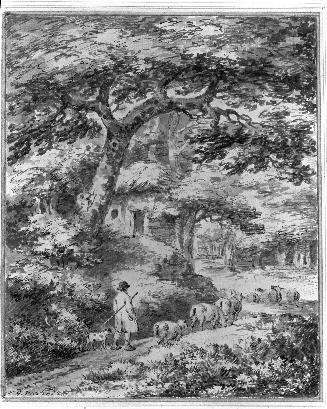

Apart from their intriguing subject matter, these paintings are remarkable for the rich medley of colors and virtuoso handling that Morland has compressed within the diminutive canvases. The deftly applied and often thickly impasted touches that describe the foliage in The Lucky Sportsman are particularly delightful, conveying a scintillating impression of texture, movement, and light. The Unlucky Sportsman is handled with greater breadth, with the artist's brushwork appearing at its boldest and most economical in the face and proper right arm of the man facing the window. Like many of Morland's paintings, this pair was subsequently engraved. It was probably Morland himself who copied the figural group from The Lucky Sportsman into the lower left foreground of A View in the Lake District, a landscape by his close friend and frequent collaborator, John Rathbone (c.1750-1807). The expansive mountain scene gains a note of human interest from the addition of Morland's colorful group, but the figures themselves lose the complex undertones that they possess as part of this pair.

Status

Not on viewObject number58.4