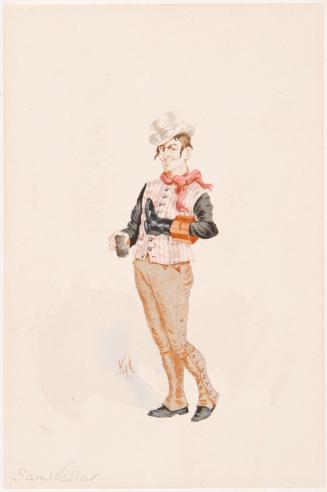

Sam with Sam Chifney, Jr., Up

Maker

Benjamin Marshall

(British, 1767-1835)

SitterSitter:

Sam Chifney , Jr.

(British, 1786 - 1854)

Collections

ClassificationsPAINTINGS

Date1818

Mediumoil on canvas

Dimensionscanvas: 40 1/8 × 50 1/4 in. (101.9 × 127.6 cm.)

frame: 48 3/4 × 58 3/4 × 4 1/4 in. (123.8 × 149.2 × 10.8 cm.)

SignedSigned and dated lower left: Sam. B. Marshall pt 1818

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Label TextSam Chifney, Jr., was born in 1786, the younger of two sons of the famous jockey Sam Chifney, Sr., and his wife, a daughter of the Newmarket horse trainer Frank Smallman. Relentlessly instructed in his father's idiosyncratic riding techniques, the boy began to distinguish himself as a jockey in his early teens. In 1802 he joined Perren's stables at Newmarket where his patrons included Thomas Thornhill (1780-1844) of Riddlesworth Hall, Norfolk, who became a good friend. In 1812 Chifney married his boss's daughter and, buoyed by success, left Perren's stables to work independently. Among many classic races, he won the Oaks Stakes at Epsom in 1807, 1811, 1816, 1819, and 1825. He won the Derby at Epsom in 1818 and 1819, riding Thomas Thornhill's horses on both occasions. In this portrait, Chifney appears in Thornhill's white-bodied jacket with red sleeves, astride the racehorse that Thornhill named for him: Sam, a chestnut colt foaled in 1815 by Scud out of Hyale. Chifney rode his namesake to victory in the Derby Stakes, May 28, 1818. The horse went on to win two minor races at Newmarket on October 26, 1818, and April 15, 1819, and placed second or third in five other races, but his career was short-lived. Sold to a Mr. Charlton in 1819, he was retired to the stud at Ludlow, where he sired at least four racehorses. Chifney's career proved more enduring. He won his last classic race, the One Thousand Guineas Stakes, in 1843 at the age of fifty-seven on Thornhill's Extempore. Through audacious betting coups, Chifney netted huge profits for himself and his patrons. In gratitude, a group led by the Duke of Cleveland built Chifney a grand neo-classical house in Newmarket, where he indulged his growing taste for lavish expenditure and indolence. Rather than starve off the ten to twenty pounds added each winter to his five-foot, six-inch frame, Chifney increasingly declined profitable riding opportunities. Financial hardship in the early 1830s forced him to sell his opulent home, but on his death in 1844, Thomas Thornhill (who had remained a loyal friend) left Chifney his Newmarket house and stables for life. In November 1851 Chifney moved to Hove on the Sussex seaside, where he died on August 29, 1854. The words "Of Newmarket" provided the only epitaph on his headstone. In 1812 Ben Marshall left his urban London studio and re-established his painting practice in the vicinity of Newmarket race course, where he immersed himself in the sporting life that provided the principal subject matter of his art. As he reportedly told his pupil Abraham Cooper, "the second animal in creation is a fine horse, and at Newmarket I can study him in the greatest grandeur, beauty and variety." Marshall is said to have been in the habit of setting up his easel in the stable of his friend, the jockey Sam Chifney, Jr., where the lighting was good and he had direct access to horses. In the present painting, as in many of Marshall's works, the horse claims center stage and is depicted in hyper-realistic anatomical detail that immediately arrests the eye. This emphasis on the animal's underlying muscles and skeleton probably reflects Marshall's conscious emulation of George Stubbs (1724-1806), whose dissection work, documented in The Anatomy of the Horse (1766), introduced a new level of sophistication to equine portraiture. In the majority of Stubbs's paintings, however, anatomy is allied to the artist's instinctive naturalism and psychological insight. Marshall, by contrast, pursued anatomy as an end in itself, privileging his abstract knowledge of equine structure over his subjective impressions of a particular animal. Here, the racehorse Sam is presented in the diagrammatic fashion characteristic of Marshall's paintings, with emphasis placed on the network of muscles, bones, and tendons beneath his flesh, and the range of colors created by the play of light and shadow on his shiny red coat.

Marshall observed details of dress and equipage with the same acute and literal eye--faithfully noting the red silk trim on the horse's blanket and the laces of the jockey's boots--but without sacrificing the vigor of his paint handling. The freedom and directness of his method is borne out in contemporary anecdotes concerning the speed with which he worked and his preference for using his thumb, rather than a brush. His dashing confidence is most impressive in the figure of the groom stepping forward at left with a checkered rug draped over one arm. Applying touches of red and white over the gray underpainting, Marshall briskly picked out the highlights and carnations of the groom's face, suggesting the moisture of sweat and the flush of excitement. The irregular shape of his mouth (open to reveal a flash of white teeth) implies that the groom is speaking to the horse as he gestures and gazes toward him.

As in many of his paintings, Marshall conceived of the foreground figures as foils to one another. Here, the straining concern of the groom is offset by the relaxed poise of the jockey, who turns his head impassively toward the viewer. Sam Chifney, Jr., was famous for his phlegmatic calm and for perfecting his father's technique of "waiting" a race. Sitting back in the saddle with the reins held loosely in his hands, he husbanded his horse's energy until precisely the right moment, when he would make a formidable dash toward the finish line--a technique famous as "the Chifney Rush." The incisive quality of this portrait reflects Marshall's long friendship with Chifney. He first painted the jockey in about 1807, the year of his inaugural Oaks victory. In the present portrait, Chifney's likeness is based on an oil study that Marshall carried out on a single canvas along with studies of rival jockeys William Wheatley and James Robinson, winners of the Derby in 1816 and 1817, respectively. Painted directly from the sitters, these studies presumably served as models when Marshall was called upon to repeat successful compositions for other patrons, or when a fresh racing victory occasioned a new portrait of the jockey with his winning horse. The ability to paint from the oil study, without troubling his human subject for additional sittings, was particularly desirable in the case of Chifney, whose dislike of posing led Marshall to remark, "Never easy, Mr. Chifney, when you're near an easel."

The present portrait was occasioned by the unexpected victory of the racehorse Sam in the Epsom Derby of 1818. It had proven a particularly difficult race and a stunning example of Chifney's riding skills. The previous month, Sam had lost his first race, the Riddlesworth Stakes, to Sir John Shelley's horse Prince Paul. Ten days before the Derby, Sam's erratic performance led his owner Thomas Thornhill to consider hedging his bets. On the day, there were ten false starts, in five of which Prince Paul (the favorite at 2-1) took the lead, only to be pulled up and returned to the gate. The sixteen unsettled horses went on to run the course in a blinding cloud of dust that enabled Chifney to creep up inch by inch before shooting forward with electric force, winning the race by three parts of a length. Odds against Sam had been 7-2, netting Thornhill an estimated £1,890, which was then a considerable sum.

Marshall's portrait purports to document the aftermath of the race, with the distant winning post visible between Sam's front legs. As in the majority of Marshall's portraits, his vividly individualized approach to the human figure enlivens the scene and invests it with a kind of narrative quality. The background teems with a dispersing crowd of two dozen figures: mounted jockeys, grooms, and spectators. Even on this minute scale, Marshall's acute eye for character and detail lends many of the heads the quality of portraiture. Undeterred by the monotonous appearance of the flat, treeless terrain, Marshall used color and texture to enliven the stubbly foreground. He charged the big sky with an impression of motion and drama by countering passages of blue with vigorously scrubbed clouds of violet-gray and pink. The three figures in the foreground are linked by light-catching strokes of pale yellow repeated in the rug, the sunlight framing the horse's head, and the jockey's breeches. A visible pentimento indicates the altered placement of the jockey's crop, which once rose diagonally from Chifney's right hand. Subtle observations and adjustments such as these attest to the fastidious care that underpins Marshall's lively evocation of a day at the races.

Status

Not on viewObject number58.2

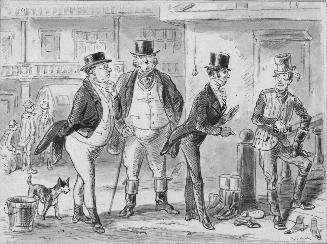

Hablot Knight Browne (called PHIZ)

n.d.

Object number: 80.7.2