Arabella (Yarrington) Huntington

Maker

Oswald Hornby Joseph Birley

(British, 1880-1952)

SitterSitter:

Arabella (Yarrington) Huntington

(American, 1850s - 1924)

Collections

ClassificationsPAINTINGS

Date1924

Mediumoil on canvas

Dimensions50 x 40 in. (127 x 101.6 cm.)

DescriptionSubject is full-front three-quarter length, seated in French gilt and embroidered tapestry armchair in front of dark background. Dressed in black silk dress and hat with veil pulled aside to reveal face and dark rimmed spectacles; wearing black jet beads and drop earrings. Hands lightly crossed in lap, covered by sheer black lace fingerless gloves.

SignedSignature

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Label TextArabella Duval Yarrington was born in the early 1850s, a daughter of Catherine J. and Richard Milton Yarrington, a machinist who died in Richmond in 1859. In the late 1860s she moved with her family to New York, where on March 10, 1870, she gave birth to a son, Archer Milton Worsham, to whom she would remain intensely devoted for the rest of her life. Endowed with beauty, intelligence, and magnetic charm, she attracted the interest of the wealthy New York railroad magnate Collis Potter Huntington. It was presumably Huntington's seed money that she parlayed into millions of dollars in the late 1870s and 1880s, chiefly through real estate and securities transactions that pitted her against William H. Vanderbilt, John D. Rockefeller, and other prominent New York powerbrokers. She devoted large sums to art collecting, filling her house on West 54th Street with progressive French landscapes by the Barbizon school and Aesthetic Movement furnishings by Herter Brothers. After years of rumors, she finally married the recently widowed Collis Huntington on July 12, 1884. During their marriage, she spent long periods in Europe, where she made extensive art acquisitions. The tremendous fortune she inherited on her husband's death in 1900 enabled her to shift her collecting to Old Master paintings, chiefly seventeenth-century Dutch, eighteenth-century French, and early Italian. Most notably, in 1907 she purchased (through the art dealer Joseph Duveen) $2.5 million worth of fine and decorative arts from the Rodolph Kann Collection. She was also a motivating force behind the British paintings collection formed by her deceased husband's nephew, Henry E. Huntington, whom she married at the American Church in Paris on July 16, 1913. She took great interest in the botanical gardens at her second husband's house in San Marino, California, but continued to gravitate toward New York. Her generous philanthropic gifts (almost all in memory of Collis Huntington), benefited such institutions as the Harvard Medical School, the Hampton Institute, the City of San Francisco, The American Geographical Society, and The Hispanic Society of America. Following a long period of illness, she died in New York, on September 16, 1924.The stern expression, direct gaze, and strong, unidealized features of this portrait were virtually without precedent in Oswald Birley's female portraiture when he painted Arabella Huntington in 1924. His approach to women was generally far less probing, tending to eschew personality and character in favor of a more superficial evocation of elegance, beauty, and sophistication. Arabella Huntington had already been represented in that sort of suavely flattering manner many years before, when, as a glamorous young beauty, she posed for her first major portrait in 1882. The French academic painter Alexandre Cabanel (1823-89) had emphasized her chic flourishes of dress and deportment as she leaned casually on a carved and gilded chair, unfurling a fan and turning her head imperiously to one side. Dressed in a striking combination of red and black that emphasizes the exposure of a good deal of creamy white skin, she presented an alluring combination of luxury, vanity, and self-assurance. Forty years later, when she sat to Birley, Arabella Huntington's circumstances had changed. She was now not only one of the richest women in the world, but also figured among America's foremost art collectors. Rather than call attention to her feminine charms in an effort to seduce the viewer, she now sits back and scrutinizes us. Shrouded entirely in black and seated before a nebulous backdrop, she reveals little of herself, presenting an impressive, but entirely impassive and enigmatic figure.

The appearance of this portrait was undoubtedly shaped by the sitter's consciousness of the purpose for which the painting was intended. By this date, her second husband, Henry Edwards Huntington, had devised a plan to bequeath his house and library to the state of California in order to form what is now the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. He commissioned Birley to paint the present portrait and a pendant of himself with the intention that they would be on display when the institution opened to the public. Arabella Huntington's recognition of the posthumous function of the portraits reportedly caused her to balk when her husband first broached the subject in 1923. "If we are painted now," his valet recalled her saying, "It will look as though we want to open this house to the public right away. We hope it will be a long time yet." As it happened, illness prevented her from sitting to Birley during the autumn of 1923, and it was not until mid February 1924 that the painter arrived in San Marino to carry out his commission.

According to Henry Huntington's valet (who claimed to have witnessed the first sitting for the present portrait), Birley had initially adapted Arabella Huntington's likeness to his glamorous feminine formula--to her immense irritation. Referring to the pendant portrait that Birley had just completed of her husband, she reportedly complained, "You painted Mr. Huntington very well, as he is today. You took all my wrinkles away, you have made me young. Why, the people will call me a fool." This would not have been the first occasion on which she had rejected a portraitist's conception of her; in 1892, she returned a painting to Roxina E. Sherwood so that her eyes could be improved by making them darker and brighter. In the present instance, however, it was her explicit desire that her portraitist not flatter her, but instead employ the same incisive characterization that he had used in painting her husband, and that he also employed in portraits of the powerful East Coast millionaires who had been her peers in business and collecting. In fact, Birley's success as a portraitist rested on his forceful and direct portrayals of powerful and distinguished men. Thus, when the present painting was exhibited at the Duveen Gallery in New York in March 1924, it was no small compliment for the critic Peyton Boswell to observe that Birley "paints elderly women vastly better than he paints young ones. His presentation of Mrs. Henry E. Huntington is on the same plane as his men."

The bold impact of this portrait owed much to Birley's emulation of the Spanish painter Diego de Velázquez (1599-1660). The predominant concern with tone and radical economy of paint handling in Velázquez's work had placed him at the center of progressive art theory and practice during the latter half of the nineteenth century, and by the early twentieth century his paintings were commanding phenomenal prices among American collectors. A Velázquez acquired in 1886 was one of Arabella Huntington's first purchases from Joseph Duveen, who became her preferred art dealer (and, through her agency, her second husband's as well). It was Duveen who had recommended Birley as their portraitist, and on seeing the present painting, he telegraphed his enthusiastic approval, stating, "It is finest portrait of modern times and as great as any Velasquez." The reminiscence of Velázquez would have held a personal resonance for the sitter, owing to her beloved son Archer's fascination with Spanish culture. It was for his sake that she bought Velázquez's Count-Duke of Olivares for the large sum of $400,000 in 1909, presenting it the following year to The Hispanic Society, which Archer had founded in 1904.

Like the Huntingtons, Birley was a great admirer of Velázquez's work, which had exerted a formative influence on his style. Here, he adopted that artist's characteristic technique of dramatically illuminating a darkly clothed figure against a shadowy background. The effect dramatizes the chill pallor of Arabella Huntington's skin, the sparkle of her jet necklace, and the glowing gilt frame of her elaborately carved chair--an actual piece from her collection, which emblematizes her collecting practice and, specifically, her taste for eighteenth-century French art and furniture. Birley's bravura paint handling also recalls Velázquez, for example in the rough, unblended strokes of color used to block in the features of his sitter's face, and in the dashes of dry white paint which convey the sparkle of her earrings and necklace. Her arresting gaze gains a lifelike quality from touches of white used to suggest the moisture of her eyes and the light reflecting off her dark-rimmed spectacles.

The dark scheme of this portrait enabled Birley to demonstrate his skill in eliciting a range of subtle distinctions in color and texture from a radically limited palette. But the unrelieved black of Huntington's silk gauze dress, net mitts, and crepe-veiled hat was not Birley's choice, but his sitter's. Since the death of her first husband in 1900, she had persistently dressed in mourning attire, a custom she refused to alter on remarriage to Henry Edwards Huntington. Her conscious self-presentation as a widow may have been calculated to evoke a regal air, for it echoed Queen Victoria's decision to remain in mourning several decades after the death of her husband, Prince Albert. Arabella Huntington defined mourning on her own terms, however. While swathing herself in black (a color flattering to her pale skin), she disregarded strictures against lavish ornament and sparkling jewelry. Freely indulging her love of luxury, she made extravagant purchases of jewels and clothing and, as late as October 1922, sent dozens of black crepe, chiffon, and velvet gowns by Worth of Paris and other exclusive designers to a New York dressmaker for alterations which included ornamentation with lace, fur, feathers, and diamond and jet beading. While the conventional masculine uniform of her husband's portrait coincides with his simple, straightforward presentation, Birley uses Arabella Huntington's idiosyncratic dress and inscrutable gaze to reinforce his characterization of her as a highly complex and rather cryptic individual.

Soon after this portrait was complete, Arabella Huntington resolved to give it to her son, Archer. With the assistance of a member of staff, whom she swore to secrecy, she reportedly removed the portrait from the wall and wrote on the back, "I give this picture to my dear son, Archer Huntington." The initials still visible on the stretcher "A.D.H./A.M.H./1924" (Arabella Duval Huntington/Archer Milton Huntington) probably represent her actual, rather more succinct dedication. Because she now intended to give the portrait to her son, she immediately began arranging for a copy to be painted, to replace the original at San Marino. Acting as intermediary, Duveen asked whether Henry Huntington would permit the paintings to accompany Birley when he returned to London in June, where they could be copied. His flat refusal indicates the high value that he and his wife already placed on their portraits: "Do not wish Mrs. Huntingtons portrait or mine on any account taken to England send both to no 2 east 57th Street [his wife's Manhattan address] Mr. Birley can do other two portraits when he returns to this country please see that this is done."

Arabella Huntington's death on September 16, 1924, only intensified her husband's regard for her portrait, which remained in New York (together with his own), awaiting Birley's arrival from London. Finally, on February 26, 1925, the original painting was returned to him and the copy was purchased by Archer. A few months later, Henry Huntington wrote Birley, "what a comfort it has been to me... to have such an admirable likeness of Mrs. Huntington. I wish you to realize how, along with the sympathy of my friends, you have been immeasurably helpful in my time of great sorrow." By then Huntington intended to hang Birley's portrait among a memorial display of early Italian Madonnas that had figured among his wife's favorite paintings. All of these works now belonged to Archer Huntington, but he released them for the sake of this eloquent tribute to his mother's cultural authority.

Status

On viewObject number24.14

William Blake

ca. 1801

Object number: 000.26

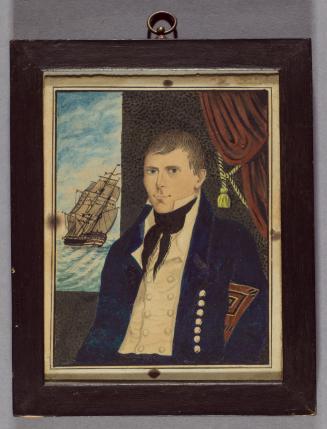

Unknown, American

early 19th century

Object number: 2022.25.12.1

Joshua Reynolds

ca.1774-1775

Object number: 23.62