Vesuvius from Portici

Maker

Joseph Wright of Derby

(British, 1734-1797)

Collections

ClassificationsPAINTINGS

Dateca.1774-76

Mediumoil on canvas

Dimensions39 3/4 x 50 in. (101 x 127 cm.)

frame: 46 1/4 x 56 1/4 x 2 1/4 in. (117.5 x 142.9 x 5.7 cm.)

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from the Frances Crandall Dyke Bequest

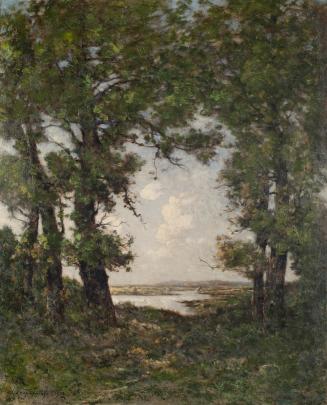

Label TextWhen Joseph Wright arrived in Italy in 1773, he had little experience as a landscape artist, although he had painted several dramatically lit night scenes. During a visit to Naples in October and November 1774, he was inspired to carry out a series of nighttime studies of Mount Vesuvius, which he declared "the most wonderful sight in nature." The last major eruption of the volcano had occurred in 1767, and since that year, according to Sir William Hamilton, "Vesuvius has never been free from smoke, nor ever many months without throwing up red-hot SCORIAE...usually follow'd by a current of liquid Lava." Wright presumably observed effects of this kind while in Naples, but certainly not the extraordinary display that he depicts in the present painting, which shows the white-hot lava shooting high into the sky. Wright probably supplemented his own on-the-spot observations with descriptions provided by Sir William Hamilton, England's "Envoy Extraordinaire" to the King of the Two Sicilies, and an ardent vulcanist. Through Hamilton and other sources, Wright could have gained access to paintings and prints of the volcano by other British and European artists, and indeed his compositions demonstrate some awareness of standard vantage points and conventions of representation.Wright's surviving sketches and correspondence indicate that he viewed the volcano with scientific curiosity as well as art historical interest. The numerous studies he carried out include a detailed pencil drawing documenting the crinkled surface of the rock face, and a large oil painting of the very summit of the volcano. In a letter to his brother, Wright noted wistfully that he would have benefited from the company of his friend John Whitehurst (an eminent scientist now regarded as the founder of modern geology), for he felt that his understanding of the volcano was inadequate. After returning to England in 1775, Wright used his studies as the basis for numerous paintings of Vesuvius (of which he is known to have painted at least thirty). Most of these are night views of the volcano in eruption, a subject that provided ideal opportunities for indulging his consuming fascination with vivid effects of light.

The Huntington painting depicts Vesuvius as seen from Portici, the location of Sir William Hamilton's villa. Earlier, Wright had made a small oil from across the Bay of Naples (L.B. Sanderson collection), but here he moves in closer so that our impression of the fiery mountain becomes more immediate. Nevertheless, we are still located at a distance that makes the volcano a scene to be contemplated, rather than a landscape that we are a part of. Through the selection of this vantage point and in several other respects, Wright sought to enhance the viewer's experience of the sublime, an ancient aesthetic concept that took on new meaning in the eighteenth century. In his influential treatise A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), Edmund Burke defined the sublime ("the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling") as "whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain, and danger, that is to say, whatever is any sort terrible." He added, "When danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and are simply terrible; but at certain distances, and with certain modifications, they may be, and they are delightful."

One of the physical traits that Burke and other commentators associated with the sublime was that of immensity. Appropriately, in this painting, Wright took particular care to suggest the tremendous size of the volcano. An obvious sense of scale is provided by the buildings that appear in the middle-distance, their domes and towers entirely dwarfed by the monstrous mountain. In the surrounding landscape, Wright used innumerable small dabs of paint to suggest the individual forms of the foliage and other landscape elements, and this minuteness further magnifies, through contrast, our impression of the towering volcano's overall mass. The blast of light generated by the eruption is also made more impressive through comparison with the pale moon that rises from the smoke and clouds at left. Wright often included a second light source as a foil to the principal illumination in his night scenes. The Eruption of Vesuvius that he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1780 prompted one critic to remark, "The different lights of the Moon, and of the Lava, contrasted by the Clouds which it raises from the Sea, have an astonishing Effect." As Judy Egerton observed in her catalogue of the 1990 Wright of Derby exhibition, the use of contrasting light sources is more understated and less artificial in the present painting than in other examples by Wright. The greater naturalism observed in this instance suggests that the artist executed the painting while his direct impressions of the scene remained fresh. For this reason, Egerton considers the present work one of the earliest (if not the earliest) of Wright's extant paintings of Vesuvius. The date of 1774-76 proposed here reflects her reasoning, while leaving open the possibility that the picture was carried out soon after Wright's return to England.

Judy Egerton has further suggested that the Huntington painting may be identifiable with a picture belonging to Wright's friend John Leigh Philips, sold from his collection in 1814 as An Eruption of Vesuvius, destroying the Vineyards. However, a letter from Wright to Philips dated February 19, 1794, makes clear that the artist was working on Philips's painting in late winter of 1794, whereas the Huntington painting, as noted earlier, appears to be a much earlier work. Moreover, Wright mentions in his letter that he has just added "forked lightning" to the sky and is about to add figures as well. An unpublished memoir written by Wright's niece confirms both the late date of the Philips painting (describing it as the last Vesuvius her uncle painted) and the appearance of the painting as "a near view, with figures as high up the mountain as was safe during an eruption, which he considered the finest he had painted." On the basis of this evidence, the Huntington painting cannot be identified with the Philips painting, and its early provenance remains unknown.

Egerton is very likely correct in surmising that the smoking fields seen here at the foot of the mountain are intended to represent the burning of the rich vineyards that surrounded Vesuvius. Indeed, the straightforward, almost offhand depiction of that episode (which occurred around the time of Wright's Neapolitan sojourn) may well have provided the model for the artist's later, more theatrical presentation of the incident in his painting for Philips, with its forked lightning and death-defying figures. In both instances, Wright's demonstration of the destructive power of the volcano, seen in combination with its awesome beauty, underpins the viewer's experience of the sublime.

Status

On viewObject number97.27

Terms