Scene from Don Quixote: Sancho Panza Entertains the Duchess

Maker

John Vanderbank

(British, ca. 1694-1739)

Collections

ClassificationsPAINTINGS

Date1735

Mediumoil on panel

Dimensionspanel: 15 7/8 × 11 13/16 in. (40.3 × 30 cm.)

frame: 2 1/4 × 18 × 2 in. (5.7 × 45.7 × 5.1 cm.)

SignedSigned and dated lower left: J. Vanderbank. fecit 1735

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Label TextOwing in part to his profligate lifestyle and restless temperament, John Vanderbank failed to achieve the triumphs as a portraitist and history painter that his precocious abilities and expertise in drawing the human figure had led many to expect. Nevertheless, a vivid impression of his potential is glimpsed in numerous vivacious drawings for unrealized historical subjects, and in small, swift, and spirited paintings such as the two panels discussed here. The present paintings relate to Vanderbank's designs for a lavishly illustrated edition of Miguel de Cervantes's celebrated novel Don Quixote (1615). This four-volume edition was published in 1738 (in the original Spanish) by J. & R. Tonson, under the patronage of John, Baron Carteret. Louis Chéron (with whom Vanderbank had set up classes for studying the life model in 1720) had previously designed illustrations for Tonson's editions of Racine (1723) and Plutarch (1724-29), and it was probably to him that Vanderbank owed his commission to contribute to the Cervantes volumes. In preparation for the sixty-eight illustrations to Don Quixote, Vanderbank produced at least three sets of drawings, the majority of which are dated from 1726 to 1730. This was clearly a time-consuming project, spanning as many as fifteen years from the first of Vanderbank's drawings in 1723 to the ultimate publication of the book in April 1738, twenty months before the artist's death. Vanderbank lived in and out of debtors' prison during at least six of those years, and the laboriousness of the Tonson project can only have added to his financial difficulties. When, at the end of 1729, his debt was cleared (for the time being) and he moved to a fashionable section of London near Cavendish Square, he found a sympathetic landlord who refused his cash in preference for anything he cared to paint, principally "Storys of Don Quixot." Vanderbank thereafter produced a large number of oil paintings based on the designs he had made for Tonson's edition of the book. The sheer number of these pictures suggests that he was not only producing them for his landlord, but seeking to capitalize on a larger market, created by the phenomenal English enthusiasm for Cervantes's novel. Don Quixote's piquant humor and poignant sentimentality proved immensely popular with a rising middle-class readership, which relished Cervantes's ground-breaking elevation of realism, comedy, and the low-brow to the epic level traditionally reserved for the ideal, tragic, and aristocratic. This new literary public also generated a market for small pictures whose topical or narrative subject matter offered immediate and virtually universal accessibility. British artists found in Don Quixote a wealth of subject matter of precisely the type that appealed to this emergent source of patronage, which they supplied with a steady stream of modest paintings, drawings, and engravings of Quixotic themes.

Vanderbank executed the two Huntington paintings (and others like it) in a broad, summary style that differs markedly from the smoother, more tightly controlled handling in his commissioned portraits. This altered manner undoubtedly reflects the greater speed with which the Don Quixote paintings were executed, but their spirited manner also evokes the lively tone and vernacular idiom of Cervantes's narrative. Vanderbank sustained this fresh quality by approaching the paintings as impromptu reinterpretations (rather than slavish copies) of his designs for engraving. The variations and experiments he pursued in the present two pictures attest to his fertile inventiveness as a designer and painter.

Plate 12 in Tonson's edition shows Sancho Panza counting Don Quixote's teeth following an altercation with a band of almond-hurling shepherds, who are shown in the background with their flock. As in the Huntington painting of the same subject (68.1), Vanderbank's exceptional academic training, and particularly his skills as a draftsman, are exemplified in the complicated and expressive poses of the central figures. In the engraving, however, our attention is distracted from these figures by the obtrusive presence of the shepherds and by the placement of Sancho's donkey, Dapple, immediately behind its master's elbow and Don Quixote's resting hand--creating a highly confusing juxtaposition. Vanderbank has improved upon this arrangement in the Huntington painting, concentrating our attention more narrowly on the two central figures by moving the shepherds into the distance and placing Dapple a bit further back. The oblique position in which the donkey is now placed required a sophisticated exercise in foreshortening, which Vanderbank appears to have tossed off effortlessly with a few strokes of thin paint. Here, and in his rendering of Don Quixote's horse, Rocinante, Vanderbank was probably aided by the close life-studies of horses that he had carried out in preparation for his illustrations to Twenty Five Actions of the Manage Horse (1729).

Despite the impressiveness of his designs for engraving, the full measure of Vanderbank's skill as an artist is revealed only in the oil medium. Although he had never traveled abroad, he made good use of the Old Master paintings available to him in England and was credited with being the first British painter to emulate Rubens's famous portrait Helena Fourment. In the present work, the atmospheric landscape backdrop is equally suggestive of Rubens. The organization of the painting is essentially carried out through color, with a foreground composed of somber earthtones opening up to the cool blues and greens of the scenic backdrop. In addition to providing an economical and effective means of delineating spatial recession within the painting, the bipolar organization alludes to two different moments in time, with the pastoral landscape providing a shorthand reference to Don Quixote's battle with the shepherds, and the foreground scene of Sancho inspecting his master for damaged and missing teeth indicating the battle's aftermath.

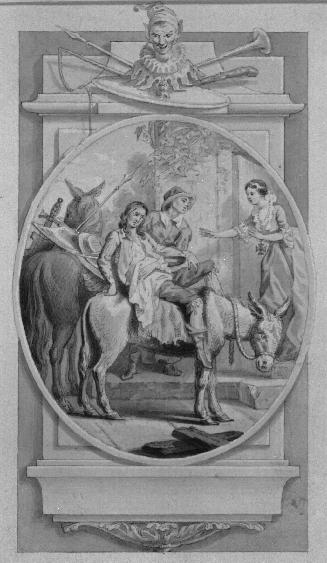

The episode represented in the second Huntington panel, based on plate 44 in Tonson's edition, is also invested with a dramatic flair that reflects Cervantes's own vivid description. Sancho Panza has just been asked a probing question by the duchess who is shown seated in the company of her damsels and duenna. Before answering, Sancho "rose from his chair and, with his back bent and a finger on his lips, went all around the room lifting the draperies." After satisfying himself that there were no eavesdroppers, he finally confessed to perpetrating a number of hoaxes against his master, Don Quixote, whom he believes to have lost his wits. Here, too, the oil medium allows Vanderbank to achieve maximum effect with minimal means. The three-dimensionality of the space is summarily indicated by the intersection of the thinly washed wall and ceiling, with a pair of curtains to demarcate the middle ground. The shimmering white satin of the duchess's gown, vigorously painted with strong highlights of white and grey-blue shadows, lends an impression of luxury to the austere setting.

The attractiveness of this female figure seems to have made this design one of Vanderbank's more popular, for he painted it in oil on at least one other occasion. In that work, he more closely followed the composition of the engraving, placing all three of the attendant figures to the left of the duchess, with the shrouded duenna relegated to a more marginal position relative to the group. Deviating from the engraving, he blocked off spatial recession by closing the curtains in the middle distance. The alternative solution adopted in the Huntington painting enhances the dramatic character of the episode by ringing the attendant women more closely around the central figure of the duchess, so that their contrasting reactions can be compared at once. The arrangement also creates a starker division between the group of women and Sancho, who is now isolated in the foreground. In both paintings, the more tightly compressed space focuses our attention on the expressions and gestures of the figures.

Tonson's edition of Don Quixote was motivated by the desire for greater fidelity to Cervantes's original text, which, since the seventeenth century, English translators had falsified through embellishment of its slapstick and ribald elements. Without eroding the book's humor, Vanderbank's illustrations nevertheless demonstrate a remarkable departure from the broad, clownish burlesque previously found in illustrations of the novel. His paintings and engravings treat the characters with a new sympathy and dignity that anticipate the emerging conception of the nobility of Don Quixote as the tale of a long-suffering knight, whose purity of aim compensates for his foolishness and delusion. Vanderbank was ideally suited to embody this new conception. His academic training had equipped him to treat the human figure in a heroic mode and his work in portraiture had made him sensitive to the subtleties of human expression. Cervantes's novel provided him with an ideal means of conjoining the idealizing, epic mode of historical composition (at which he excelled, but for which there was little market), with a vernacular, comic, and often sentimental idiom that afforded wide appeal. As such, Vanderbank's innovative paintings provide a prescient foretaste of future developments in British art.

Status

Not on viewObject number68.2

John Vanderbank

1735

Object number: 68.1