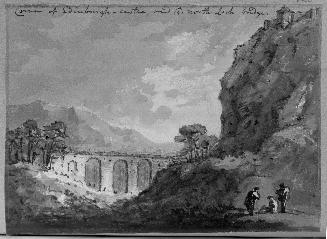

Edinburgh, from St. Anthony's Chapel, Arthur's Seat

Maker

Unknown

Additional Title(s)

- Edinburgh, from Saint Anthony's Chapel, Arthur's Seat

Collections

ClassificationsPAINTINGS

Dateca.1830-1836

Mediumoil on canvas

Dimensions34 × 44 3/4 in. (86.4 × 113.7 cm.)

frame: 46 × 56 1/2 × 5 in. (116.8 × 143.5 × 12.7 cm.)

46 × 57 × 5 in. (116.8 × 144.8 × 12.7 cm.)

DescriptionA high slope on the left, leading to Arthur's Seat, a volcanic protrusion in Edinburgh, Scotland; Edinburgh castle silhouetted against the sky, beyond; the crowned church tower of St. Giles; the old prison, on an abrupt cliff, just right of center; above it, to the right, the high school, the Nelson Monument, and Waterloo Memorial; below them, in the middle ground, Holyrood Palace.

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Label TextDuring the eighteenth century, Edinburgh's reputation as a vital intellectual, scientific, and cultural center caused it to be dubbed "the modern Athens." An ambitious building program in the first decades of the nineteenth century crystallized analogies between the modern Scottish city and its classical Greek prototype. Atop the 350-foot rise of Calton Hill (seen to the right in the present painting) numerous monuments were erected, chiefly in honor of military and cultural achievements. The hill of monuments put many viewers in mind of the Acropolis rising above the city of Athens, leading cynical critics to disparage the city's new structures as "instant ruins." Civic pride was a more prevalent response, however, and widespread interest in the city's new developments created a market for publications such as John Britton's Modern Athens! Displayed in a series of views; or, Edinburgh in the nineteenth century (1829), which purported to exhibit "the whole of the new buildings, modern improvements, antiquities and picturesque scenery of the Scottish metropolis and its environs." In the present painting, the artist's intention is clearly the same as Britton's--to call attention to the rich array of ancient and modern monuments that ornament Edinburgh's dramatic terrain. The view was taken from Arthur's Seat, a volcanic formation rising 823 feet above sea level in the southern part of Edinburgh. This scenic overlook had long been popular among artists as well as casual visitors, such as those seated in the immediate left foreground, resting beside the fifteenth-century ruins of St. Anthony's Chapel. In the left distance is the ancient heart of the city, Castle Rock, with the towers of the castle rising above the spires of several churches: St. Giles, Tron, St. Patrick, and St. George. In the right distance is Calton Hill, newly embellished by such features as the neo-classical Royal High School (1825-30), the Burns Monument (1825-30), the Nelson monument (1816), and the National Monument (1822), modeled on the Parthenon of Athens. At the foot of the hill is Holyrood Palace and the ruin of Holyrood Abbey. Conspicuously absent from the painting is the Scott monument, erected between 1836 and 1846, which would have stood in the central distance of the present view. Its absence suggests that the painting was executed in the early 1830s.

Despite the impression of objectivity created by the artist's topographical style, he has selectively emphasized only some of the monuments, minutely picking out their details, while adjacent buildings dissolve into hazy obscurity. Similarly, in the foreground landscape, large passages are merely sketched in with thin washes of paint, creating a raw, undifferentiated appearance that suggests they remain unfinished. Yet, the artist has taken the trouble to embellish these passages with myriad tiny details, such as the figures walking along the paths in the left foreground and the tombstones dotting the hill at far right. These would normally be the very last touches added to a nearly completed painting, for there would be little sense in adding them to areas that had yet to be finished. Pervasive disparities in degrees of detail and finish indicate the artist's expectation that viewers would shift their focus from one scenic highlight to another, without dwelling on the filler space between them. This splashy, theatrical approach differs entirely from the unified effects pursued in landscape paintings intended to hold up under sustained scrutiny.

A sense of disjunction also characterizes the spatial structure of the composition. Adopting a common device, the artist employed a dark, undifferentiated foreground to throw the eye back onto the brightly illuminated middle-distance and background, where a series of overlapping planes chart recession into depth. The distant prospect has something of the two-dimensional flatness of a theatrical backdrop, however, and the challenging topography of the city results in spatial ambiguity and confused perspective. Particularly disruptive is the rising contour of Salisbury Crags in the central middle distance, which interrupts the viewer's imaginative entry into deeper pictorial space.

Rather than a coherent view, the painting presents a kind of highlights tour of Edinburgh, dwelling exclusively on features that would merit mention in a guide book. Depicting the city from a sightseer's perspective, the artist privileges entertainment value over conventional artistic concerns with unity, balance, completion, and so on. The same approach was adopted in popular media, such as touristic prints and theatrical scene painting, as well as more innovative pictorial forms such as the panorama, a mass entertainment that debuted in Edinburgh and made the city its first subject. The earliest of these monumental wrap-around paintings was displayed by the Edinburgh artist Robert Barker (1739-1806), who in 1787 lined the interior walls of a circular building with a 360-degree view of the city's remarkable architecture and topography. The panorama spawned alternative illusionistic displays, such as the diorama and the peepbox, in which artificial lights cast onto a two-dimensional scenic backdrop directed the viewer's eye to certain portions, or created the impression of movement and changing times of day. Many of the artists who produced these illusionistic forms of popular entertainment also painted scenic backdrops for the theater, which were similarly reliant on strong perspectival effects and striking topographical and architectural points of interest. The visual expectations that shaped such popular forms of art also seem to underpin the present painting, which was probably produced by an artist versed in creating touristic and theatrical images for mass consumption. This painting may represent his attempt at producing a more conventional work of art.

When the painting entered the Huntington collection in 1937, its inconsistencies in handling were disguised by an old coat of yellowed varnish that suffused the landscape in a warm, glowing atmosphere. The painting was then attributed to J.M.W. Turner, one of the great masters of British landscape. The attribution to Turner was rejected by Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll in 1977 on the grounds of the painting's confused perspective, uncharacteristic handling, and somber palette. When the discolored varnish was removed in 1981, it became still more apparent that the painting could not be by Turner. Although the identity of the artist remains unknown, the peculiarities of style and intention discussed here provide important clues for making that determination.

Status

Not on viewObject number37.1