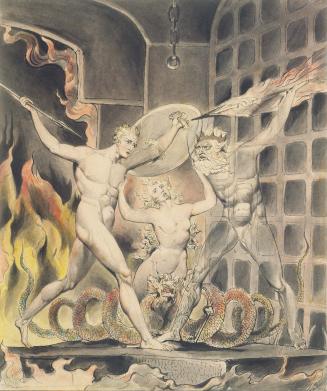

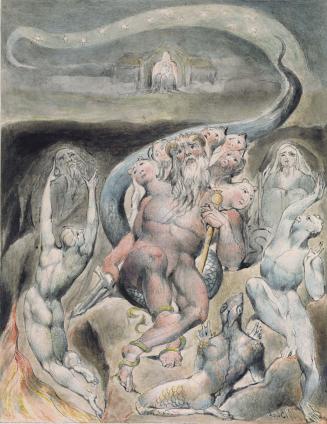

Illustration to Milton's "Paradise Lost": Satan, Sin, and Death: Satan Comes to the Gates of Hell [large version]

Maker

William Blake

(British, 1757 - 1827)

Additional Title(s)

- Illustrations to "Paradise Lost" [no. 1 of 1, large version]

- Paradise Lost: Satan, Sin, and Death: Satan Comes to the Gates of Hell [large version]

- Satan, Sin and Death: Satan Comes to the Gates of Hell [large version]

ClassificationsDRAWINGS

Date1808

Mediumpen and watercolor, with touches of gold metallic paint [now tarnished] on wove paper

Dimensions19 1/2 × 15 3/4 in. (49.6 × 40 cm.)

DescriptionThis version of "Satan, Sin, and Death" became detached from the other designs in the Butts series of illustrations to Paradise Lost when the group was dispersed at auction in 1868. Ten of the other eleven Butts illustrations are signed "W Blake" and are dated 1808; but it is possible that this design was executed as an independent work at a slightly earlier date, perhaps even before the other version in the Huntington. Blake rarely used the distinctive monogram appearing on this design after 1806. [1] "Satan, Sin, and Death" is the only design in the series with this monogram, and the only one touched with liquid gold. A lapse of time might also explain the inconsistency of picturing Death without a beard, for he is shown with a long, flowing beard in the tenth and eleventh designs of the Butts series.

For a discussion of motifs and comparisons with other versions, see the other "Satan, Sin, and Death" below.

Notes

1. See Butlin 1972-73, 45-46; Butlin, "Cataloguing William Blake" in Blake in His Time 1978, 82-83; Butlin 1981, 385.

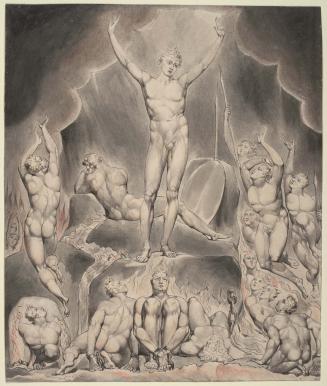

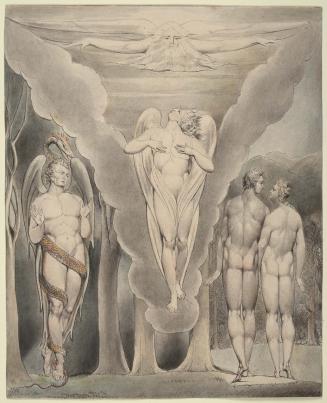

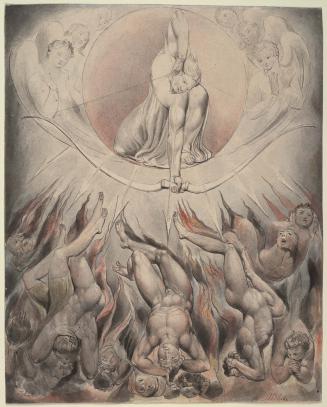

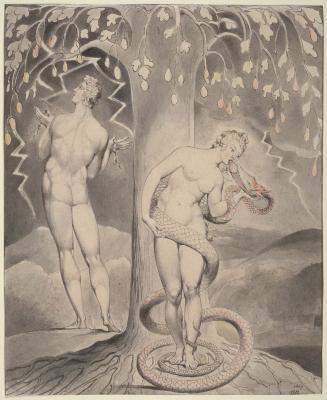

Satan, in his flight to the earth, enters from the left to be challenged by his incestuous offspring, Death (2:645-734). Sin, Satan's daughter and mate, interposes herself between father and son (2:726). The basic arrangement of the figures follows the tradition established by William Hogarth's painting of ca. 1735-40 and continued by many illustrators of the scene. [1] In Blake's first known attempt at the subject, a pencil and wash drawing of ca. 1780 (University of Texas, Austin; Butlin 1981, No. 101), Satan and Death are pictured much as in this Huntington design, but Sin is on the right. A pencil drawing at Johns Hopkins University (Butlin 1981, No. 530) is closely related to the finished watercolors and is probably of about the same date. It is close in size to the Thomas/Huntington version with the figures similarly proportioned, but Satan and Death stand as in the Butts/Huntington design. This drawing may be transitional between the two watercolors, with Sin's arms arranged in an intermediate position. Rossetti 1863, 249, No. 99, and 1880, 268, No. 127, lists an uncolored work he titles "Death shaking the dart" in the collection of "Mr. Harvey." This untraced drawing may be related.

Satan brandishes the shield and spear pictured at his side in the first design, even though neither is mentioned in the passage illustrated. The adversaries "frown" and take "horrid strides" toward each other (2:676, 713-14). Death, wearing a "kingly Crown," raises his flaming "Dart" with both hands and levels "his deadly aim" at Satan's head (2:672-73, 711-12). Milton describes Death as a "shadow," a figure "that shape had none" (2:667, 669). Most illustrators of the scene pictured him as a skeleton, but Blake indicates Death's insubstantiality by drawing his body in outline but revealing the background through his transparent flesh. Blake has thereby remained true to the text without turning away from his characteristic linear style and toward chiaroscuro techniques indicative of the "obscurity" which, for Edmund Burke, made Milton's description of Death an exemplar of the sublime. [2]

The strong diagonals formed by the combatants' weapons give linear expression to their conflict and focus attention on Sin, who rises to separate them. She is pictured with a voluptuous torso, but below her loins are the tails of two serpents coiling "in many a scaly fold/Voluminous and vast" and the heads of three "Hell Hounds…/With wide Cereberean mouths" (2:650-51, 654-55). Her "fatal Key" to "Hell Gate" (2:725) dangles to the right of Death's right calf. Above and behind Satan are two archways, suggesting that he has already passed through two groups of the "thrice threefold" gates and has come to the last set "of Adamantine Rock" (2:645-46). Although the rectilinear gateway on which the figures stand suggest rock, the barrier on the right is, as in Hogarth's painting, a "huge Portcullis…/Of massy Iron" (2:874, 878) with vertical bars terminating at the bottom in points like Death's dart. The chain descending above the center of Blake's illustration also recalls the chain hanging from the portcullis in Hogarth's picture, as well as the chains in Blake's first design.

In the Butts version, also at the Huntington, Satan has his left leg forward and is turned more toward the viewer. His genitals are scaled. Death, now without a beard, has his left foot advanced and shows us his back. Sin's left arm is almost fully extended to touch Death's left elbow. The scaly coils on each side terminate in crested serpents' heads similar to the snake's in the ninth design. Their open mouths and forked tongues recall Milton's image of "a Serpent arm'd/With mortal sting" in the scene illustrated (2:652-53). The same detail appears, rather obscurely represented, in Burney's illustration published in 1799. The head of a fourth hellhound now appears just left of Satan's left knee. All three figures stand on uneven ground rather than cut stone. The vertical bars of the portcullis no longer end in spear-points. There are numerous minor changes in the figures' hair, the architectural background, and in the position of the flames.

For further information on the Butts version, see Part I, section A, No. c, below.

Notes

1. See David Bindman, "Hogarth's 'Satan, Sin and Death' and Its Influence," Burlington Magazine 112 (1970): 153-58. Blake could have known Hogarth's design, now in the Tate Gallery, through any of three eighteenth-century engravings. The same format appears in the illustrations of the subject by James Barry and Henry Fuseli, two artists whom Blake admired. Butlin 1981, No. 529.2, suggests that Barry's Satan in his engraving of ca. 1792-95 influenced Blake's portrayal of Death, and that several of Fuseli's treatments of the subject influenced Blake's Satan.

2. See Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, ed. James T. Bolton (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1958), 58-59.

SignedSigned on lower left with Blake's monogram: inv. / WB

InscribedInscribed on verso not in Blake's hand [now covered under backing mat]: drawn for Mr. Butts from whom it passed to Mr. Fuller.

Signed in lower left with Blake's monogram: inv. / WB

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Label TextThis drawing is one of Blake’s illustrations to Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost. It depicts the scene when Satan, on the left, arrives at the gates of Hell to battle Death, his own incestuous offspring. Death’s mother, Sin, the daughter of Satan, tries to separate them. Their expansive gestures and intense facial expressions enhance the drama of the scene. Strong diagonals created by the bodies of Satan and Death and the weapons they wield focus attention on Sin’s voluptuous figure, surrounded by serpents and hellhounds. In his depiction of Death, Blake closely follows Milton’s text, which describes him as a shadow, by painting him as if he were transparent (2022).

Status

Not on viewObject number000.3

Terms

William Blake

1807

Object number: 000.2

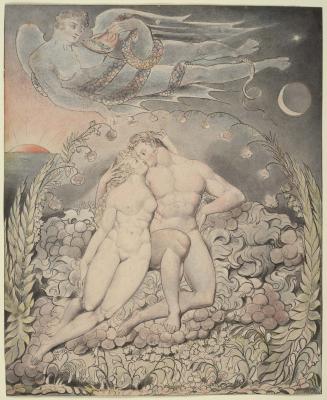

William Blake

1807

Object number: 000.6

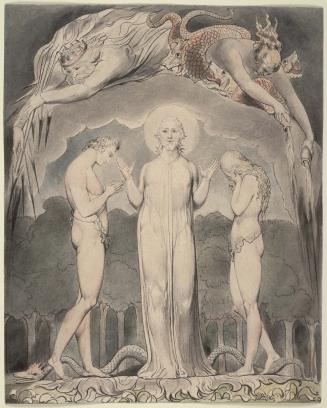

William Blake

1807

Object number: 000.11

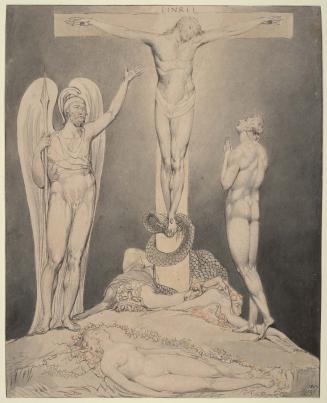

William Blake

1807

Object number: 000.12

William Blake

1807

Object number: 000.4

William Blake

1807

Object number: 000.1

William Blake

1807

Object number: 000.5

William Blake

1807

Object number: 000.7

William Blake

1807

Object number: 000.8

William Blake

1807

Object number: 000.10

William Blake

ca. 1814-1816

Object number: 000.16

William Blake

ca. 1814-1816

Object number: 000.18

![Illustration to Milton's "Paradise Lost": Satan, Sin, and Death: Satan Comes to the Gates of Hell [large version]](/internal/media/dispatcher/39206/preview)