Salome

Maker

Paul Manship

(American, 1885-1966)

Collections

ClassificationsSCULPTURE

Date1915

Mediumgilt bronze on marble base

Dimensions18 1/4 x 13 3/8 x 10 1/4 in. (46.4 x 34 x 26 cm.)

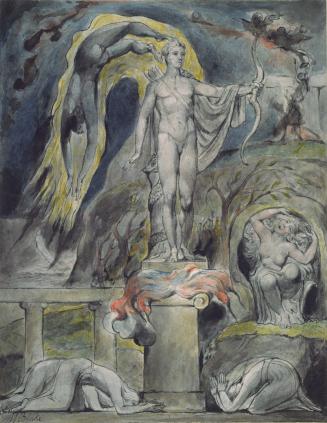

DescriptionPaul Howard Manship's stylized and decorative sculptures from the second decade of the twentieth century diverged dramatically from the more naturalistic, academic works of Beaux Arts sculptors such as Daniel Chester French and Frederick MacMonnies whose sculptures can be seen in the main gallery of this building. Born in St. Paul, Minnesota, Manship attended the St. Paul Institute of Art and, in 1905, moved to New York where he enrolled in the Art Students League and assisted Solon Borglum in stone carving projects. Manship continued his studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, in Philadelphia; but, in 1908, he returned to New York and began working as an assistant to the sculptor Isidore Konti. In 1909, Manship won a three-year scholarship to study sculpture at the American Academy in Rome. While in Rome, he traveled widely and studied the works of Greek and Roman antiquity. He discovered archaic Greek art and, after his return from a trip to Greece in 1912, he presented a paper entitled The Decorative Value of Greek Sculpture, in which he celebrated "the power of design, the feeling for structure in line, the harmony in the division of spaces and masses" in pre-classical Greek sculpture. Manship attracted widespread attention with the works he showed in his first exhibition at the Architectural League of New York, in 1913, an event that coincided with the notorious Armory Show. In recognition of his debt to archaic Greek sculpture, critics, struck by the linear stylization of the hair and drapery on his statuettes, labelled Manship's style archaistic.

The New Testament story of Salome dancing lasciviously for king Herod, who had promised to give her whatever she wanted in exchange for this favor, was a subject of endless fascination in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, receiving ghastly tribute in a play by Oscar Wilde, an opera by Richard Strauss, illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley, and paintings by artists as diverse as Franz von Stuck and Robert Henri. Manship's Salome is one of his most exotic works and may have been influenced by Léon Bakst's designs for the Ballett Russe and contemporary dance performances. The decorative treatment of form, the freely flowing, graceful and rhythmic contours, and the simplicity and planar orientation of Manship's figure found parallels in a choreographic style that had been developed by modern dancers such as Ruth St. Denis, Maud Allan, and Isadora Ducan. Salome demonstrates how Manship, drawing inspiration from pre-classical and non-Western sculpture, rejected naturalistic description for flattened form and simplified, abstract shapes. His love of ornamental detail is evident in the wealth of jewelry and the richly-bordered skirt worn by the dancer. The decorative and stylized patterns of the hair, eyes, jewelry, and heavy draperies cascading from her shoulders suggest archaic Greek sources. The mannered gestures and angular pose also reflect the sculptor's interest in the art and dance forms of India, which began to receive serious attention from art historians around 1910. Manship's early success owed much to the way in which his work married the classical and the abstract, placing him between modernists and traditionalists.

SignedSigned in upper right: Paul Manship / 1915

InscribedSigned in upper right: Paul Manship / 1915

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation

Copyrightcopyright © Estate of Paul Manship

Label TextManship's Salome is one of his most exotic works and may have been influenced by contemporary dance performances. The decorative treatment of form, the graceful and rhythmic contours, and the planar orientation of the figure have parallels in modern choreography, such as that of Isadora Duncan. Salome also demonstrates how Manship rejected naturalistic description for the flattened form and simplified, abstract shapes of Modernism. The decorative and stylized patterns of the hair, eyes, jewelry, and heavy draperies, by contrast, suggest archaic Greek sources. Manship's success was due in part to the way his work married the classical and the abstract, the Modernist and the traditionalist.The New Testament story of Salome dancing for King Herod, who then promised to give her in recompense whatever she wanted, fascinated writers, composers, and artists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries: Oscar Wilde, Richard Strauss, Aubrey Beardsley, and Robert Henri all treated the subject.

Status

Not on viewObject number95.20

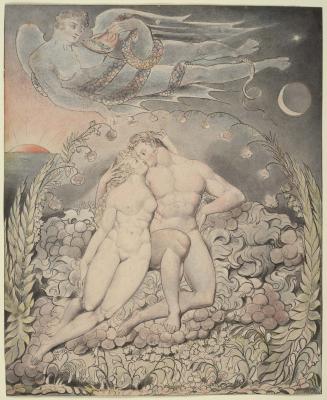

William Blake

ca. 1814-1816

Object number: 000.17

William Blake

1807

Object number: 000.6