Dr. Isaac Schomberg

Maker

Thomas Hudson

(British, 1701-1779)

SitterSitter:

Dr. Isaac Schomberg

(British, 1714 - 1780)

Additional Title(s)

- Man in a Gray Coat

Collections

ClassificationsPAINTINGS

Dateca.1750-1760

Mediumoil on canvas

Dimensions29 5/8 x 24 3/4 in. (75.2 x 62.9 cm.)

DescriptionDr. Isaac Schomberg (1714-1780), well-known physician. Half-length, facing viewer at nearly full face. Dressed in green-grey velvet coat and waistcoat, with white lace at collar and sleeves. White powdered wig, tied back with bow of same color as coat. Proper left hand tucked into waistcoat, hat secured under the arm. Plain, dark background. Painted oval format.

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Label TextIsaac Schomberg, a physician, was born at Schweinsberg, Germany, on August 14, 1714, one of eight children of Meyer Löw (1690-1761), who assumed the name Schomberg around 1715. The family settled in London in 1720, where the senior Schomberg became one of London's most successful physicians. Isaac obtained his M.D. from the University of Leyden in 1745, and early in 1747 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, in pursuit of a second medical degree. In February 1747 his rash response to a summons for examination from the Royal College of Physicians (the body responsible for granting medical licenses to London doctors) initiated a twenty-year feud. Denouncing Schomberg's letter as "improbable and indecent," the College suspended his medical practice. He nevertheless continued to see patients, and fanned public interest in his case through anonymous pamphlets and a series of legal hearings held between November 1751 and July 1753. In 1761 he became co-heir of his father's estate along with his brother Sir Alexander Schomberg (1721-1804), a captain in the Royal Navy (their five brothers were cut off with a shilling each). On December 23, 1765, Schomberg at last received his medical license, but not until September 30, 1771, was he admitted as a fellow of the College of Physicians. Notwithstanding his professional difficulties, Schomberg attained a high position among London physicians, was an active Freemason, and a subscriber of numerous publications. In 1779 he attended his friend David Garrick on his deathbed and among the actor's final words were those addressed to Schomberg: "Though last, not least in love." Schomberg died unmarried at Conduit Street, London, on March 4, 1780, and was buried at St. George's church, Hanover Square.A doctor might understandably wish his portrait to convey an impression of dignity and restraint, but Isaac Schomberg, the subject of this painting, had particular reasons for insisting on his professional gravitas. A Jew born and educated abroad, Schomberg faced certain prejudice in his profession in England. His difficulties were magnified by his quarrel with the Royal College of Physicians, which forced him to practice medicine without a license for over two decades. Schomberg's Christian baptism in 1747 and his naturalization as an English citizen in 1750 demonstrate his determination to assimilate to his adoptive country and its forms of respectability. This portrait provides further evidence. With his hat secured under one arm and his hand tucked into his vest, Schomberg's pose is a textbook illustration of stately formality. His dress, too, is calculated to create an impression of quiet dignity. He wears an ultra-conservative wig whose artificial shape dispenses with nature and fashion together. Discreet ruffles of fine lace appear at his neck and wrist, and his subdued velvet coat (with inconspicuous buttons of the same material) is made still more understated by his wearing it with a matching velvet vest. The tight fit through the upper torso and sleeves reflects the fashionable English cut of the late 1750s.

The early history of this portrait is unknown. It is first documented by William P. Sherlock's stipple engraving, published in the European Magazine on August 1, 1799, with the inscription "Dr. Isaac Schomberg/ From an Original Picture Painted by Hudson/ in the Possession of J. Edwards, Esq." There is no reason to question the identification of the sitter or owner, but the name of the artist comes as a surprise. In some respects, the painting corresponds with what we know of Hudson. Several of his signed portraits present their subjects within a feigned oval, the body oriented to one side and the face turned toward the viewer. However, Hudson's touch is rarely so nuanced as it appears here--for example, in the subtly modeled facial contours and the scarcely perceptible transitions from glinting highlights to deep shadow. In Hudson's portrait of John Newton, executed around the same time (c. 1757-60), the facial features have hardened into mask-like rigidity, and the patches of highlight and shadow stand out in marked contrast. The sensitive use of chiaroscuro in Schomberg's portrait finds closer analogies in the work of Allan Ramsay or Joseph Wright of Derby. In particular, the sparkle of light caught in the sitter's blond eyelashes recalls the same effect in another portrait in the Huntington collection, once attributed to Ramsay and now believed to be by Wright.

It is possible that Sherlock's print (published about four decades after the painting was made) carries an erroneous inscription. But the question is complicated by the collaborative nature of London studio practice during the mid-eighteenth century. A collection of artists' working drawings in the Derby Museum provides evidence of extensive practical cooperation between Hudson, his occasional assistant Ramsay, and his student Wright. The commingling of these artists' hands in numerous paintings of the 1740s through 1750s manifests a different notion of authorship from that which pertains today. It would not have been unusual for Wright (who worked for Hudson from 1751-53 and from 1756-57) or another painter affiliated with the workshop to have finished this portrait under Hudson's supervision and in his name. The multiple layers of opaque paint and transparent glazes (which Hudson rarely used) hint at this sort of intervention for the purpose of mollifying the overall effect. Some of Hudson's late portraits suggest that he and his assistants were deliberately cultivating this softer appearance in the 1750s.

The connection with Hudson is buttressed by the fact that he had previously painted Schomberg's father, seated at a table with his chin resting thoughtfully in one hand and a quill pen in the other, pausing in the act of writing (A.C.B. Schomberg, Esq.). Meyer Schomberg made no secret of preferring Isaac to his brothers (a favoritism dramatized by the terms of his will), and he may have commissioned Hudson to paint his son as well as himself. However, there are other possibilities. Isaac's generosity and "warm benignity of soul" were gratefully acknowledged by friends such as William Hogarth, who gave Schomberg first editions of his engravings and painted his brother (and co-heir) Alexander in 1763 (National Maritime Museum, London). Schomberg was Hogarth's physician as well as his friend, and these works of art were possibly quid pro quo for medical attention--the sort of arrangement that Thomas Gainsborough adopted with his physicians, among them Isaac's twin brother, Dr. Ralph Schomberg (1714-1792). Perhaps Thomas Hudson was another artist who benefited from Isaac Schomberg's friendship and medical expertise and reciprocated pictorially. It would not be the first instance in which a painter's affection for a friend yielded a portrait of exceptional sensitivity.

Status

On viewObject number33.1

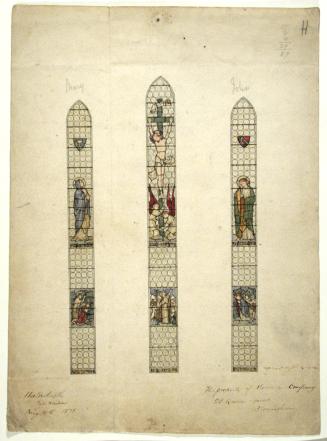

Edward Burne-Jones

ca. 1871

Object number: 2000.5.1234

Edward Burne-Jones

ca. 1927

Object number: 2000.5.980

![Portrait of a General [Duke of Schomberg (?)]](/internal/media/dispatcher/4904/thumbnail)