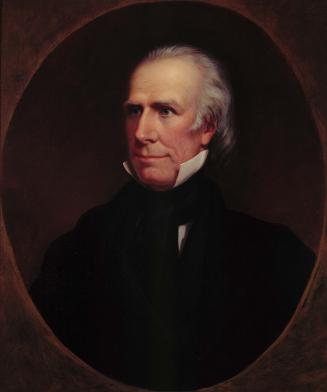

Henry Edwards Huntington

Maker

Oswald Hornby Joseph Birley

(British, 1880-1952)

SitterSitter:

Henry Edwards Huntington

(American, 1850 - 1927)

Collections

ClassificationsPAINTINGS

Date1924

Mediumoil on canvas

Dimensions50 x 40 in. (127 x 101.6 cm.)

SignedSignature; Date

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Label TextHenry Edwards Huntington was born on February 27, 1850, in Oneonta, New York, the fourth of seven children of Harriet (Saunders) and Solon Huntington (1812-90), a merchant. Completing his formal education at the age of seventeen, Huntington spent the 1870s pursuing unrewarding work in hardware stores in New York and sawmills in West Virginia. On November 17, 1873, he married Mary Alice Prentice (1852-1916), a niece by marriage of his uncle, Collis Potter Huntington. From 1881-85 he oversaw the laying of railroad track in Kentucky and Tennessee on behalf of Collis, who arranged for him to become superintendent of the Kentucky Central Railroad Company in 1885. A keen bibliophile, Henry Huntington began to collect rare books after moving to San Francisco in 1892, where he became first assistant to his uncle (then president of the Southern Pacific Company of San Francisco). When Collis died in August 1900, Henry (along with his uncle's widow, Arabella [Yarrington] Huntington) inherited a sizeable portion of the estate. Increasingly enamored of southern California, he devoted the 1900-10 period to developing electric street railways in Los Angeles, speculating in real estate, and developing the ranch property in San Marino that he had purchased in 1903 (now The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens). The house he built there from 1908-10 was decorated with Arabella Huntington's advice, and under the supervision of the art dealer Joseph Duveen, who encouraged Henry to embark on an ambitious scheme of art collecting. Having been divorced in 1906 on grounds of desertion, he married Arabella on July 16, 1913, to the dismay of his children and the amusement of the press. He had largely retired from business in 1910 and increasingly devoted his attention to his San Marino property and collections which, out of affection for his adoptive home of southern California, he ultimately transferred to the state as "a free public library, art gallery, museum and park." Following his death on May 23, 1927, he and his second wife (who had died three years earlier) were buried together in a mausoleum on the grounds.From New York on January 27, 1923, the art dealer Joseph Duveen fired off an enthusiastic telegram to his client, Henry Edwards Huntington in San Marino: "Wonderful artist here Oswald Birley who has painted some great portraits in England.... He already has one commission in California and would go there if he could secure another." Huntington was accustomed to receiving such overtures from Duveen, whose acute eye and shrewd negotiation skills had provided him with the greatest masterpieces in his collection of historical British paintings. However, disappointment with a previous portrait commission that Duveen had orchestrated led to Huntington's terse refusal: "Do not care to have another portrait painted without seeing the artists work." As often happened, Duveen's powers of persuasion gradually coaxed a change of heart, and on February 8, 1923, the dealer expressed his delight that "at last [you are] going to have [a] really great portrait." Birley and Huntington met in New York that summer, and in mid February 1924 the artist, accompanied by Duveen himself, arrived in San Marino to carry out portraits of Henry Huntington and his second wife, Arabella.

Birley's fundamentally conservative style, formed through close study of European Old Masters, yielded "an eminently `safe' rather than an inspiring" mode of portraiture, but one recognized for "good ideas of arrangement and a masculine bluntness of statement that won respect." He had already painted numerous British aristocrats, socialites, and military men by the time he met Duveen in 1922. The dealer's aggressive promotion of Birley's career swiftly propelled him to prominence as a leading painter of fashionable and official portraiture. On his arrival in America in 1923, Duveen assisted Birley in obtaining commissions from J. Pierpont Morgan, Andrew W. Mellon, John Hay Whitney, Charles Dana Gibson, and other men and women of note. Among the influential New Yorkers to whom Duveen introduced the artist was Archer Milton Huntington (1870-1955), an aficionado of Spanish culture who had founded The Hispanic Society of America in 1904. Birley shared Archer's interest in Spanish painting, particularly the art of Diego de Velázquez (1599-1660). The year Birley spent in Madrid in 1905 (during which he systematically copied portraits by Velázquez) had exerted a seminal influence on his style. The reminiscence of Spanish painting in Birley's portraiture evidently struck a chord with Archer, who, according to Duveen, was "full of praise for his work." It was ostensibly at his suggestion that Duveen contacted Archer's stepfather, Henry Huntington, about the possibility of his sitting to the painter.

The pair of portraits that Birley produced for the Huntingtons provides a striking instance of Velázquez's sustained influence on British portraiture over three-quarters of a century. Beginning in the late 1850s, French-trained artists active in England, most notably James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), had found confirmation for their own progressive tendencies in Velázquez's tonal emphasis and radical economy of brushwork. His robust, alla prima technique (working directly on the canvas, without preliminary studies) provided them with an authoritative antithesis to the laborious preparatory methods of academic convention. By the close of the century, allusions to Velázquez had become a commonplace in the fashionable portraiture of artists such as John Singer Sargent (1856-1925). Henry and Arabella Huntington were among the American collectors caught up in the vogue for Velázquez. After purchasing the painter's Portrait of A Young Ecclesiastic in 1911, Henry proudly singled it out for special notice in an interview concerning his collection that year. Arabella had purchased a Velázquez in 1886 (her first acquisition from Duveen), and in 1909 she paid an enormous sum for his Count-Duke of Olivares.

In the present work (and its pendant), Birley emulated Velázquez in placing the dark figure against a shadowy backdrop and adopting a somber, nearly monochromatic color scheme. As in prototypes by Velázquez, this arrangement allowed Birley to experiment with subtle harmonies of low tone. The bold blocking of the head, with minimally blended contrasts of pigment, highlight, and shadow, recalls Velázquez's alla prima technique. However, evidence suggests that Birley actually used a grid to transfer the composition to his canvas, implying that at this early stage in his career, he superficially evoked the effects of bravura spontaneity, while actually employing the more painstaking academic methods that he had learned at the Académie Julian in Paris. Nevertheless, Birley's progress was evidently quite rapid. According to Henry Huntington's valet, Alphonso Gomez, this portrait required just six sittings, "and it was complete, it was perfect, and they were very pleased."

The mirroring poses and somber, nearly monochromatic color schemes clearly link Birley's two portraits of the Huntingtons as a pair. However, the artist also elaborated important distinctions between them. Henry's presentation recalls the most straightforward conventions of British portraiture, particularly his own first major acquisition of this type, Henry Raeburn's full-length Sir William Miller, Lord Glenlee of c.1805-15. It, too, is a dark, nearly monochromatic painting of an older man dressed in a sober, conservative fashion, seated indoors before a paneled wall. The subjects of both paintings are portrayed as alert and politely welcoming, but with subtle undertones of impatience. Raeburn shows Glenlee turning momentarily from a desk piled with documents, and Birley makes equally clear that Huntington is not lounging, but perched temporarily, with spine erect, hands clenched in tense readiness, knees spread in anticipation of standing.

Birley updated the early nineteenth-century conventions of Raeburn's portrait through the progressive formal concerns of tone, atmosphere, and economy that later British artists had imbibed from Velázquez. The elaborate setting of Glenlee's portrait is swept away so that the sitter appears in isolation, without the distractions of color, spatial recession, or narrative props. Expansive areas of crimson in Raeburn's portrait have been condensed into the tiny red buttonhole in Huntington's lapel--the only strong color accent in the painting. The stark presentation rivets our attention on the sitter, and particularly on his psychologically charged head and hands, whose eye-catching pallor stands out in relation to the somber browns and blacks of the rest of the painting. The head and hands are further emphasized by the bright white shirt collar and cuffs, with slightly greater attention drawn to the face through the tiny accents of the red buttonhole and lustrous black-pearl tie pin.

The great pains that Birley took in lending Henry Huntington's face and body precisely the right character are revealed in a letter from Duveen criticizing the copy of the present portrait that Birley produced six months later, at Huntington's request. "In the original you have portrayed an alert healthy looking man," Duveen wrote Birley in late January 1925, whereas in the copy "the whole body looks older and sagging" and "gives the appearance of a man ten years older." He asked that Birley correct several details in Huntington's face (the "rheumy and weak eyes," wrinkles, pouchy chin, blotchy complexion), and also adjust certain effects of tone that may have been effective from an artistic standpoint, but that made the coat and trousers appear dull and rusty, and the tie and collar "smudgy." The acuteness of these observations and the firmness with which Duveen urged them sheds light on his decision to accompany Birley to San Marino in the first place. Having once made the mistake of disappointing Henry Huntington, Duveen was determined to ensure the total success of Birley's commission.

As starkly modern as the present portrait appears beside Raeburn's, it is staid and conservative in comparison with that of Henry Huntington's wife, Arabella. In lieu of the orderly rectilinear background shown here, Birley placed her before a darker, more nebulous backdrop that probably represents a curtain, but reads far more ambiguously. The straightforward perpendicular lines of Henry's body--which consist of a series of right angles--echo the linear quality of the paneling, and of the simple English side chair in which he sits. Arabella's form, by contrast, melts into a vague mass of drapery, as unfathomable as the dim atmosphere from which she emerges. The elaborately carved and gilded French chair on which she sits is composed of sinuous curves that complement the folds and swags of her drapery. The chairs in the two portraits were actually owned by the Huntingtons, and their styles reflect the sitters' different collecting practices. However, they reveal a great deal more about them than that. Henry, certainly the more conventional of the two, appears straightforward, upright, and unembellished, while Arabella, who arose from obscurity to reinvent herself many times over, presents a somewhat arcane, unfathomable, and sphinx-like appearance.

The present portrait and its pendant were completed by March 10, 1924, and shipped to New York a few days later for display in an exhibition of thirty-three Birley paintings, held that month at the Duveen Galleries. A critic who saw the portrait there noted, "The artist has portrayed a keen man of finance who yet possesses as one of his major traits a passionate appreciation of the aesthetic; you see here the man who could strive to make money in order that he could spend million on millions for paintings and rare books. Mr. Birley's picture in this instance is an historical document for which the nation is deeply indebted." This assessment would have pleased Huntington, who had undertaken the portrait in expectation that it would represent him after his death, when his house and library were opened as a public institution. Birley's portrait admirably fulfills this intention, revealing not only the personality of the man, but also alluding, through its historically redolent style, to the collection of British paintings that constituted one of Henry Huntington's principal legacies.

Status

On viewObject number24.13

Joshua Reynolds

ca.1774-1775

Object number: 23.62

John Hamilton Mortimer

ca.1763

Object number: 78.8

Angelica Kauffman

ca. 1780

Object number: 2001.11