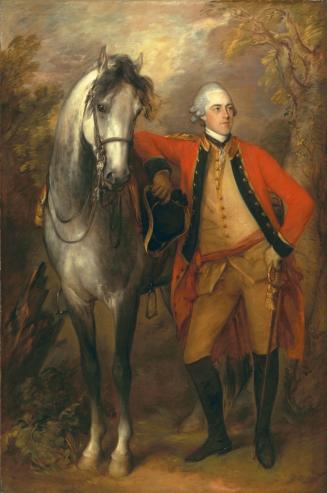

Anne (Luttrell), Duchess of Cumberland

Maker

Thomas Gainsborough

(British, 1727-1788)

SitterSitter:

Anne (Luttrell), Duchess of Cumberland

(British, 1743 - 1809)

Collections

ClassificationsPAINTINGS

Dateca. 1777

Mediumoil on canvas

Dimensionscanvas: 36 × 28 1/4 in. (91.4 × 71.8 cm.)

frame: 47 × 39 1/2 × 4 in. (119.4 × 100.3 × 10.2 cm.)

DescriptionNearly half-length, turned slightly left, the head a little to the right. Powdered hair, dressed high, showing her ears, with gray gauze scarf and pearls; large curls behind her neck. The face is a long oval delicately colored; the eyes are dark. She wears a low dress of pale vieux rose, with a lace fichu, bound with pearls, and a pearl earring and bracelets. A brown scarf of striped gauze swathes her arms and is held by both hands; the right, against her breast, has a ring on the little finger. Dark-brown background, with a deep-red curtain on the left.

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Label TextAnne Luttrell was born at St. Marylebone, London, on January 24, 1743, the eldest daughter of Simon Luttrell (1713-1787) of Luttrellstown, county Dublin, Ireland, and his wife Judith Maria, daughter and heiress of Sir Nicholas Lawes, governor of Jamaica. Successive generations of her family had gained notoriety for their outrageous conduct and she, too, would court controversy for most of her life. On August 4, 1765 she married Christopher Horton ("a sporting squire") of Catton Hall, Derbyshire. She was reportedly devastated when he died in August 1769, a few days after the death of their only child. Two years later, she began a whirlwind romance with George III's youngest brother, Frederick (1745-1790), Duke of Cumberland, who had recently been tried and found guilty of adultery with a married peeress. She married the duke secretly at her house in Mayfair on October 2, 1771 and they fled to Calais, France. The king's displeasure on hearing of this marriage (and soon thereafter of the surreptitious marriage of another brother, the Duke of Gloucester) provoked the Royal Marriage Act of 1772, which forbade members of the royal family under the age of twenty-five from marrying without the monarch's consent. For the next several years the duke and duchess were banned from court. They divided their time between England and continental Europe, where she raised eyebrows by insisting on high ceremonial treatment. Horace Walpole described her as "extremely pretty, not handsome, very well made, with the most amorous eyes in the world, and eyelashes a yard long. Coquette beyond measure, artful as Cleopatra, and completely mistress of all her passions and projects." Following the duke's reconciliation with the king in 1780, the duchess continued to attract notice by hosting lavish entertainments in London. She and her husband also traveled frequently abroad. The duchess sustained this pattern after her husband's death in 1791, spending much time in Germany and Switzerland. Her traveling companion was an unmarried cousin, Sarah Bettina Lawley, who became the principal heir to the duchess's estate on her death in February 1809 in Switzerland. Gainsborough's first acquaintance with the woman in this portrait was at Bath in 1766, when he painted her as Mrs. Anne Horton, wife of a relatively obscure member of the gentry (National Gallery, Ireland). Within five years, her scandalous, clandestine marriage to the king's youngest brother had transformed her into a royal duchess--though one who was barred from court and shunned by much of polite society. Her contested social position no doubt contributed to the ostentatious displays of wealth and status for which she became notorious. The numerous portraits she commissioned of herself and of her husband suggest a similar concern with ratifying a carefully orchestrated public image.

One of her first acts on returning to England as Duchess of Cumberland was to coax her husband into sitting to Joshua Reynolds for a pair of full-length portraits in the spring of 1772. Although the stately solemnity of these paintings was clearly calculated to entrench the sitters' claims to regal dignity, they themselves deemed the portraits unsatisfactory and never bothered to pay for or retrieve them from Reynolds's studio. The duchess proved equally troublesome to Joseph Wright of Derby. From Bath in February 1776 he complained, "The Duchess of Cumberland is the only sitter I have had, and her order for a full-length dwindled to a head only, which has cost me so much anxiety that I would rather have been without it; the great people are so fantastical and whining they create a world of trouble, though I have but the same fate as Sir Joshua Reynolds, who painted two pictures of Her Royal Highness and neither pleases."

Gainsborough must have provided the demanding duchess with what she was seeking, for the pair of full-length portraits that he painted in 1777 initiated a string of commissions from the Cumberlands. Their patronage was a mixed blessing, for certainly the duchess epitomized the self-importance that Gainsborough found so irritating in his fashionable sitters. Indeed, her concern with status caused him to falsify his own sensibilities in the full-lengths of 1777. One critic who saw them at the Royal Academy exhibition that year observed that the sitters were "pourtrayed (in compliment to their Royal Highnesses no doubt) in rather more state, than is consistent with the free, and elegant designs of this artist."

Smaller in format and more intimate in conception, the present portrait differs fundamentally from the grand, public paintings that the duchess was commissioning during the 1770s, and yet it is equally the product of the sitter's prickly vanity and status-consciousness. She is presented in the fancifully contrived drapery that Gainsborough often employed for his female sitters, but with a greater quantity of jewelry than is typical in his "fancy-dress" portraits. The heightened suggestion of wealth is more representative of the duchess's proclivities, and Aileen Ribeiro has observed that the gold signet ring on the duchess's right hand and the pearl bracelets (embellished with portrait miniatures) on her wrists almost certainly represent real items of jewelry with which the duchess chose to be represented. As bracelets of this type most frequently appear in royal portraiture (including Gainsborough's 1777 full-length of the Duchess of Cumberland), Ribeiro speculates that the jewelry is intended to signal not only the wealth of the sitter, but also her special status as a member of the royal family.

Further evidence of the duchess's intervention in this portrait is possibly provided by her hairstyle. The fleeting fashionability of the high-dressed coiffure shown here barely survived the 1770s, and would have appeared highly artificial and unflattering by the next decade. It may have been the duchess herself who had the coiffure repainted in the low, full style of the late 1780s, as she also appears to have done with Gainsborough's full-length portrait of 1777. In its revised incarnation, the present painting became well-known through at least ten exhibitions and an engraving. As described in the Technical Notes above, the repaint was finally detected and removed in 1910 and an effort was made to restore the portrait to its original appearance. Errors in the restorer's interpretation are evident in the lopsided tilt of the hair and in the lack of definition near the top of the coiffure, where it becomes unclear whether the thin grey paint depicts locks of hair or a gauzy scarf. The actual arrangement of the hair, as Gainsborough originally painted it, is probably documented by a small, roughly contemporaneous copy, in which the hair is dressed convincingly in the high style of the late 1770s.

Despite the compromised condition that has resulted from successive campaigns of cleaning and repainting, an impression of Gainsborough's original intent remains in the beautifully rendered drapery of the Huntington portrait. The remarkable subtlety and elusiveness of the dusky pink silk dress is complemented by a faintly violet-grey gauze scarf flecked with stripes of gold. The fabrics are sketched with loose strokes of the brush, which create a shimmering, evanescent quality. In this respect, the painting anticipates effects that Gainsborough would pursue in earnest during the last decade of his career, when his progressively economical brushwork relied on illusionism, rather than linear description and solid modeling. Here, rather than define the physical construction and texture of his sitter's garments, he has merely aimed at capturing their visual effect. The filmy layers that envelop the figure appear so insubstantial as to dissolve into transparency in certain passages. Greater economy of handling enabled Gainsborough to make shorter work of fashionable portrait commissions such as this, which he found onerous for personal as well as artistic reasons. However, the increasing panache of his paint handling gave him an edge over rival painters--especially in portraits of women, which he imbued with a unique, ethereal quality. His idiosyncratic methods softened even the most steely of his high-society clients, suffusing them in an aura of soft, visionary loveliness.

Status

Not on viewObject number12.10

Martin Archer Shee

ca.1804

Object number: 20.4

Joshua Reynolds

ca.1783-84

Object number: 24.33